By Joel Dresang

Maybe it’s a phase, but I’m feeling more cynical toward the relative worth of our possessions. I’m questioning the value ascribed to our chattel, especially what’s been handed down to us.

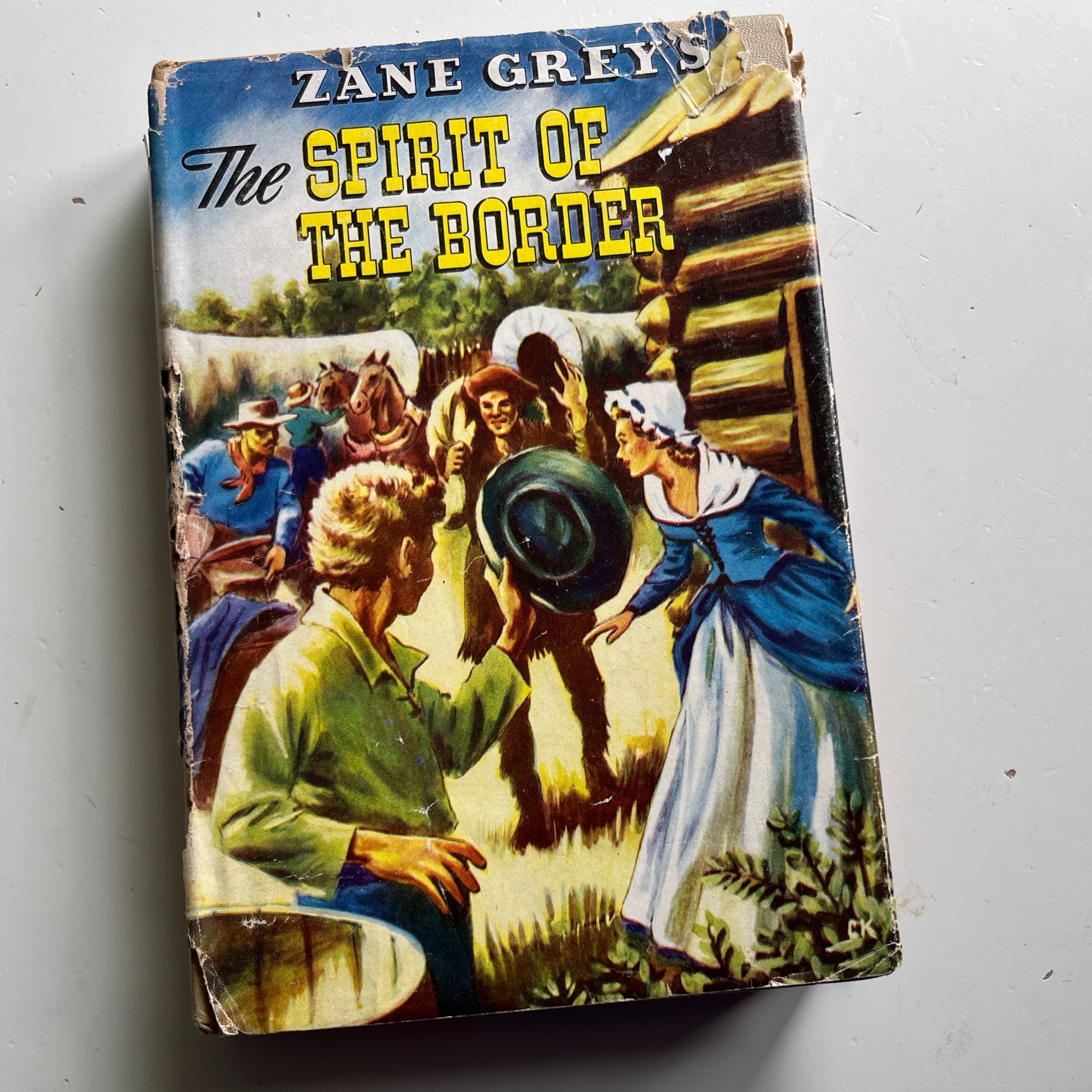

In the garage, some of the clutter I’ve clung to was my dad’s: Old push mowers, a disembodied engine, three sets of golf clubs, tangled fishing equipment, ancient tools. In the house, we have furniture and toys and books from when I grew up. I was tossing out some of those books a while back, when I encountered a copy of Zane Grey’s “The Spirit of the Border.” I never read it as a kid, but it was always in the bookcase my dad built in our living room.

The book still has a dust jacket on it, though it’s torn, but the book itself is in good condition. It looks older than time, and the copyright shows only one year, suggesting to me it’s a first edition. So, I kept it.

If I’m to be objective, I have to weigh our stuff’s value – either actual or perceived – against the cost of keeping it. In other words, is it worth the space it’s taking up? Is it worth more to someone else? Is it worth the bother of me (or my progenies) getting rid of it down the road?

As an investment advisor, Art Rothschild always ponders questions of value in the context of clients’ retirement portfolios.

Occasionally, a client will have the investment equivalent of a push mower or a Zane Grey novel in the mix of their diversified assets. Sometimes, people have holdings that make sense only to them.

“Times change, and the perception of value changes,” Art says. “Something we value today and think might be worth more in the future might actually be worth less in the future.”

That’s the experience of Paul Kennedy, too. Paul is a friend of mine who for the past 27 years has held various senior editorial roles with media companies publishing books and magazines focused on the antiques and collectibles fields. Through his work, Paul has observed how hard it is for people to be objective about their possessions.

“Everyone overvalues the objects they surround themselves with. It’s only natural,” Paul, now editorial director for Kovels Antique Trader, wrote in an email. “We make three investments when we buy something: time, money and emotion. Of these three, I would argue that emotion is the greatest investment because it is the most personal.

“For many people, the objects that surround them come to define them,” Paul explains. “That’s why it’s so difficult to let go of a collection – you lose your identity – and why people tend to overvalue what they have.”

Although managing money is mostly a rational pursuit, emotions often play a part, Art says.

“We have to be sensitive to the feelings of our clients. That’s the emotional part,” Art says.

Some investors want to hold on to certain positions more for sentimental reasons than for the sense it makes in their portfolio, Art says. For instance, some clients are attached to certain stocks because they worked at that company, or maybe they received shares as a gift or bequest. Art himself maintains separate IRAs he received from his mother and father.

Overvaluing what we have isn’t inherently harmful, but Paul has helped handle the fallout from collectors’ delusions. Recently, he says, a widow called him about her departed husband’s collection of nearly 1,000 Franklin Mint plates.

“The plates lined shelves around their home and filled unopened boxes in their basement. Her husband justified his hobby of collecting limited-edition plates by telling her they were collectible and would increase in value,” Paul says. “That’s simply not true.

“So, on top of grieving the loss of her husband, the wife is left wondering what she can possibly do with all these plates. Her options are few and none of them are good.”

In such cases, Paul says, he tries to help the caller focus on their loved one and the enjoyment they must have found in collecting.

“That really is the true value of anything,” Paul says. But he also levels with callers about the practical value of the collection.

When his clients cling to financial assets that don’t make sense from an investment perspective, Art says, he tries to reason with them. But he’ll also respect their wishes.

“It boils down to why do you own something? What is the value to you? What is the value of something else?” Art says. “That’s where you hire a professional to help you, if you want to make a decision about something.”

Paul says the same about collectibles.

“I work with people who have very extensive collections that run the gamut from incredibly valuable pieces of art to thousands of practically worthless items: think Beanie Babies,” Paul says. “With both extremes, having a realistic appreciation of the marketplace for these items is critical. And I’m not talking about what a collector paid for something. I’m talking about how much that item is valued in the marketplace today. There’s a big difference.”

Upon further review, my Zane Grey wasn’t a first edition. The copyright on the book says 1950. The book was first published in 1906.

But another of the books I salvaged from my childhood house is a Horatio Alger story, “Only an Irish Boy.” It’s in pretty good shape and much older, although a quick search on eBay suggests it isn’t worth much on the market. It still has value to me, though.

In the front of the book is a note to Gordon Peske from his mother. I remember my mom calling Gordon her favorite uncle. Mom also told me I reminded her of Gordon. Therein lies the value of that book – to me.

I’ve placed a note in the book sharing that context. Either before I discard it – or my wife or daughters do – at least we’ll have a little more informed perspective on what it’s worth.

Joel Dresang is vice president-communications at Landaas & Company, LLC.

Paul Kennedy’s advice to collectors

- Inventory what you have. Take pictures. Create a document. Objectively assess your collection’s value.

- Ask family members if there is anything they might want after you are gone. Note that.

- Then, sell or liquidate your collection sooner than later so that your family doesn’t have to deal with it when you’re gone.

“It’s always better to act too soon, while you can be part of the process and to say goodbye to your collection, respecting it and appreciating it one last time, than to procrastinate and leave the emotional and financial heavy lifting to someone else.”

More Money Talk articles from Joel Dresang

Learn more

Working With an Investment Professional, from Investor.gov

Working With an Investment Professional, from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority

Liz Weston: What to do with your stuff the kids don’t want, from Nerdwallet

How to Get Rid of Practically Everything, from Consumer Reports

Learning to unpack, unleash legacy, by Joel Dresang

(initially posted May 31, 2024)