By Kyle Tetting

A growing number of economists, including many with the Federal Reserve Board, are expressing concern over changing prices. One of the primary roles of the Fed is to combat inflation, but of late there has been more concern over an even more dangerous threat to economic recovery: Deflation.

Each month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes the Consumer Price Index, which measures the average change in price of a basket of goods and services. A meaningful increase in the CPI over the same month last year is considered inflation while a meaningful decrease signifies deflation. The Fed generally targets a year-over-year CPI increase of 1.5% to 2% as a healthy rate for a stable but growing economy.

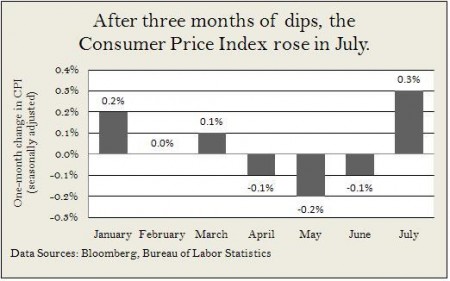

In early 2010, the CPI showed steady year-over-year price growth of 2% to 2.5%. However, three straight months of falling prices, particularly food and energy prices, slowed growth. Prices nudged up again in July, but the annual inflation rate through the first seven months stood at just 1.2%. While the CPI as a whole is growing, and as a result deflation remains only a threat, the current bout of slowing inflation – or disinflation – threatens a weak economic recovery.

Deflation can be dangerous as businesses respond to falling prices by cutting output and jobs and selling off inventory without restocking the shelves until the economic outlook becomes more certain. After all, why invest in manufacturing if the price for the end product will fall? Additionally, consumers, waiting on a better deal, may hold back purchasing non-essentials. As a result, deflation can feed off itself, causing a prolonged period of economic stagnation or worse.

Fears for now

Given the current low interest rate environment, many investors have feared what inflation would do to the purchasing power of their cash and low-yielding investments. The greater fear among some economists is what a prolonged period of deflation would do to the economy. A lack of job growth could quickly become additional job loss and a double-dip recession as a result of weakening demand.

While the Fed can raise interest rates to combat inflation, deflation has proved a more difficult foe. Lowering interest rates can serve to spur spending and push up prices, but with key interest rates already near 0%, the Fed has no room to make further cuts. As a result, the Fed will use proceeds from maturing mortgages and other sources to purchase two- to 10-year Treasuries in an effort to keep the money supply elevated. In theory, this should help to fight deflationary pressures.

While few expect a plunge in the CPI, a shallow but prolonged period of deflation would have serious consequences for consumers and businesses. Stock investors would likely see weak corporate earnings as a result of falling prices, which may equate to weak stock prices as well.

But even in a deflationary environment, companies well-positioned after a difficult recession can still find ways to be profitable. Many have lowered debt ratios, cut excess and are even sitting on piles of cash in an effort to support dividend payments. Additionally, companies producing food, medical supplies and other items more resistant to recessions would likely be less affected by deflationary pressures.

As investors flee to safety, prices in longer-term government bonds would be pushed higher while yields would fall, contributing to higher total returns for existing bondholders. Higher quality, intermediate- and longer-dated municipal and corporate bonds also would likely benefit. Additionally, cash and similar types of investments gain value as prices fall.

Further ahead

While deflation concerns are not unfounded, even those economists urging caution still admit the longer term worry is likely to be rising prices. While deflation may be difficult to battle, the Fed has every reason to reach its target inflation rate in an effort to devalue the high levels of both public and private debt.

Additionally, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke has indicated in the past that the Federal Reserve has no reservations about turning on the printing press when necessary, devaluing outstanding debt through inflation.

The next few months of CPI reports will shed some light on what has been a discouraging trend of falling month-to-month prices (disinflation, not yet deflation). Unless the trend is reversed, the Federal Reserve may be forced to take more drastic steps to fight deflationary pressures, possibly spurring inflation, rather than simply stabilizing prices.

Kyle Tetting is director of economic research at Landaas & Company.

initially posted Aug. 12, 2010 (updated April 13, 2015)