From the NBER

Frequently Asked Questions

Determination of the February 2020 Peak

Business cycle dates (back to 1854)

By Joel Dresang

Two consecutive quarters of negative GDP do not a recession make. That’s the reminder from the White House in advance of a report on U.S. economic growth.

Back-to-back declines in gross domestic product is a common quick-and-dirty description of a recession. Technically, it’s much more complicated.

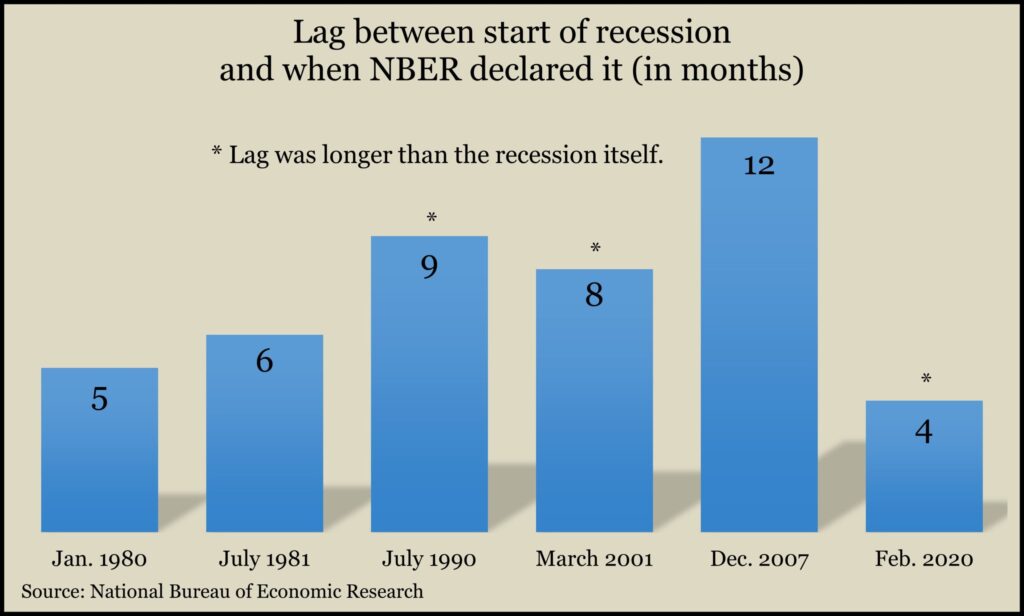

Independent academic economists forming the National Bureau of Economic Research decide when recessions officially start and end. They rely on a deep array of data, which takes months of collection and analysis. Their official declarations are the thunder after a lightning strike—a delayed confirmation of what’s already been felt.

On July 28, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis issued a preliminary estimate that GDP declined at a 0.9% annual rate in the second quarter of 2022. That followed a 1.6% setback in the first quarter, making two consecutive quarters of negative GDP.

A week in advance of the GDP report, though, the White House posted a blog explaining that economists determine recessions from a broad view of activities, including the job market, non-government spending, industrial output and income.

“Based on these data, it is unlikely that the decline in GDP in the first quarter of this year—even if followed by another GDP decline in the second quarter—indicates a recession,” the White House said in a blog posted July 21, 2022.

The White House also suggested that the decline in first-quarter GDP wasn’t an indication of broad economic contraction because it was driven by slowing inventories and a widening trade deficit. The trade gap grew in part because the U.S. has been growing faster than its trading partners, the White House said, and inventories are “one of the noisiest components of GDP growth.”

Paige Radke agreed that the measures weighing down the GDP, including housing, tend not to be long-term forces of economic doom.

“Those are not big, lasting issues that are going to extend through the rest of the economy and push us into the type of recession that we may have seen in the past,” Paige said in a recent Money Talk Podcast.

But signs of weakness and talk of downturn add to the uncertainty that stirs market volatility and can undermine investor confidence, Paige said: “We’re in this moment of flux.”

Recessions are always a question of not if but when. Though the White House maintains that first-half data don’t yet show a downturn, Paige said she works with clients to prepare their portfolios for the inevitability of recessions.

The top question Paige has been hearing lately is whether we’re in a recession or one’s around the corner.

“My answer typically is maybe, maybe not. But does it really make a difference about our long-term plan?” Paige said. “And the answer is no.”

Joel Dresang is vice president-communications at Landaas & Company.

Learn more

Math hints on bonds, balance, recession, by Kyle Tetting

First time since 2009: Recession, by Joel Dresang (2020)

Keeping balance in unnerving times, by Bob Landaas

Recessions: Uncertainty suggests balance, a Money Talk Video with Kyle Tetting

How to handle fears of recession, a Money Talk Video with Bob Landaas and Kyle Tetting

Gross Domestic Product, from the Bureau of Economic Analysis

U.S. Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions, from the National Bureau of Economic Research