Learn more

Estate Planning FAQs, American Bar Association

Estate Planning: Power of Attorney, Financial Industry Regulatory Authority

Help for agents under a power of attorney, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

5 Things to Know About Preparing a Will, Financial Industry Regulatory Authority

5 tips for naming beneficiaries, a Money Talk Video with Mike Hoelzl

When Should I …check my beneficiaries? by Art Rothschild and Isabelle Wiemero

Plans to consider, by Lexie Brown

Retirement spending with heirs in mind, a Money Talk Video with Dave Sandstrom

By Joel Dresang

I was digging through some old boxes in the basement when I found a blue three-ring binder labeled, “Estate Planning Documents.”

It was another reminder – along with the unexpected loss of one of my brothers earlier this year – that my wife and I should update our plans. For starters, the documents in the binder were 17 years old. The attorney who drafted them left the law firm seven years ago. The firm went out of business six years ago. Also, our three daughters – our motivation for the plans to begin with – are in much different circumstances than they were then.

I remember a cold, dark, weeknight sitting at the end of a long, heavy conference table at the law firm. The attorney occupied our older daughters with legal pads and pens while we grownups conferred. The older girls were 8 and 4 at the time. The youngest, a few months old, slept in her car seat.

At the end of the meeting, the attorney asked our daughters if they had questions or if they even knew what we were doing. The 8-year-old said, “Yeah. You’re making plans to die.”

That’s not how I would have put it, but she was right. And I was glad she was aware and that somehow she understood the concept that we wouldn’t always be around.

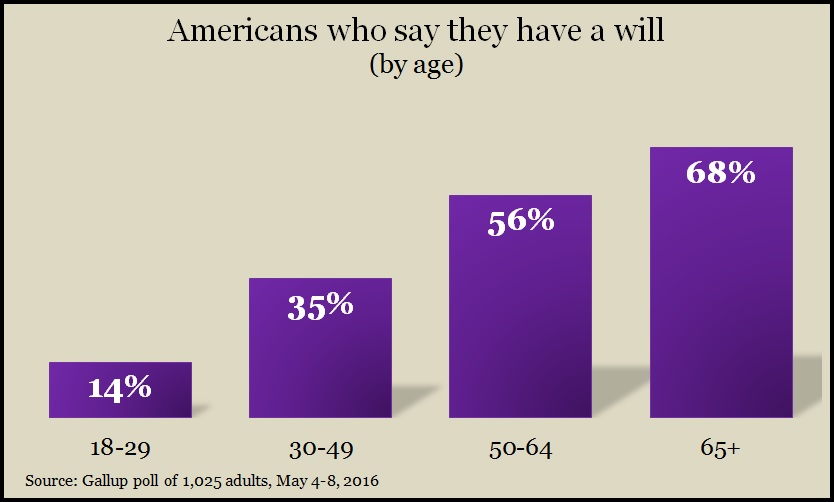

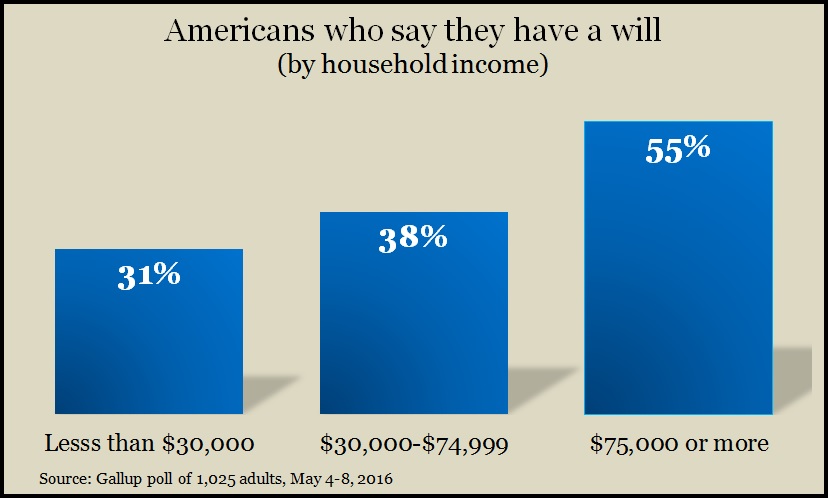

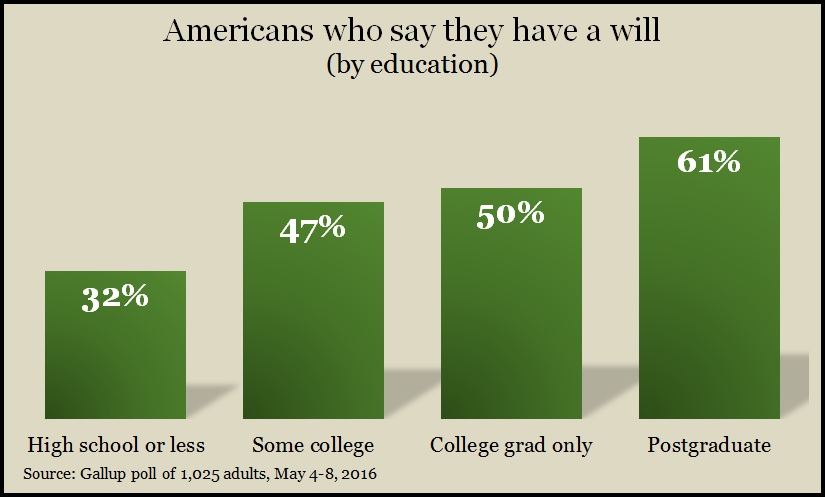

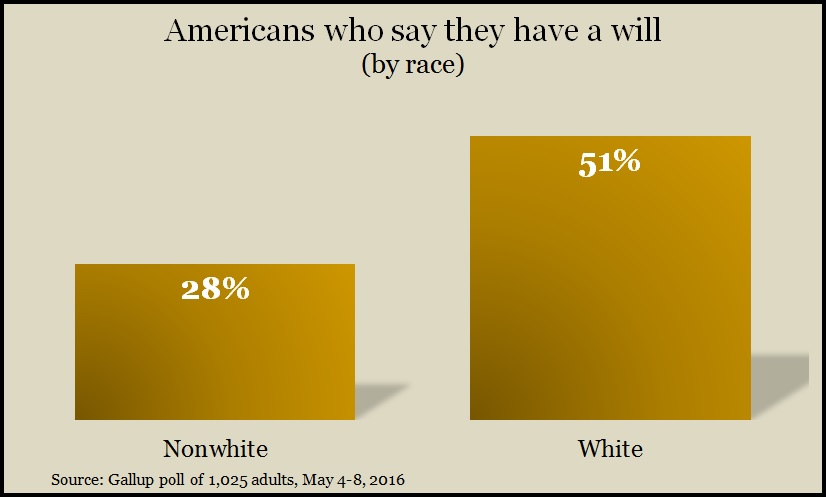

Not even half of American adults have legal plans for what happens to their assets or how their families would be provided for in their demise. A 2017 survey by Caring.com and a 2016 Gallup poll paint similar portraits of a population that overall hasn’t made plans to die.

That negligence comes from a paralyzing combination of fear and procrastination. Few want to consider their own death, let alone do anything about it. Plus, the thought of spending time and money on the task of preparing for death makes it easier to do nothing.

Common wisdom and my family’s experiences suggest you want something in place because a) it gives you some control over what happens after you die, and b) more importantly, it can make survival much easier for your loved ones. Add a) and b) together, and you get peace of mind.

Think of planning your estate like yanking off a Band-Aid: An unpleasant but necessary act that’s better approached by just getting it over with.

“This document is not a substitute for having those difficult conversations with loved ones,” our new attorney said when my wife and I met with her to revise our plans. In fact, the process has given us more opportunities to talk with our family about our end-of-life wishes. And, we have the luxury of having those conversations when we’re not on deadline – pun intended.

I know there are do-it-yourself options, but between the time involved and the risk of not doing it ourselves properly, we figured it was worth hiring an experienced attorney at an established firm for $300 an hour to get us up to date.

At this point, our financial situation is relatively simple. We have designated the girls as beneficiaries of our investment accounts. And, replacing our old wills, we have signed a marital property agreement to ease the passage of our other assets first from one spouse to the survivor and then, after the second spouse’s death, to our daughters (and their children).

In a nutshell, here are the steps we have taken:

- Engage an attorney. I tracked down the lawyer we used before, but we opted for another firm at which a couple of friends work. I first consulted with the new attorney through a no-charge 15-minute telephone conference.

- Complete a worksheet. The firm sent a five-page form asking about family relationships, assets and liabilities, legal history and our choices for financial power of attorney and health care power of attorney. The only part that took a little time was gathering information on our financial accounts and mortgage.

- Inform our daughters. We’ve asked our oldest daughter to be executor of our plan and named all three as power of attorney. We’ll explain more to them and have them sign papers when we’re together for Thanksgiving.

- Meet with the attorney. We reviewed our worksheet with her and answered questions at her office. She listened to what we wished and told us what to expect.

- Sign papers. After reviewing copies of the paperwork the firm had sent us, we met again and signed everything with witnesses.

Legally, we’re all set. I’ll follow up with those named in the 17-year-old documents to explain our new arrangements and let them know they’re off the hook.

We also have to find a place to store the new documents so they’re secure but accessible for when they’re needed. They shouldn’t be papers I happen to stumble upon in the basement 17 years from now.

We also need to resolve to revisit our situation more frequently. Our attorney suggests annual reviews with updates when life changes occur – marriages, births, disabilities, deaths, estrangements, legal issues. If nothing else, she advises, we should check in with an attorney every five to 10 years in case changes in laws would affect our plans.

Around the time I rediscovered the blue binder in the basement, Aretha Franklin had passed away with an estimated $80 million estate but no will to suggest how her wealth should be passed along. Like Prince, who died two years earlier – and an array of other celebrities including Bob Marley and Kurt Cobain – the Queen of Soul’s oversight has detracted from her legacy, possibly triggering years of legal squabbling among her survivors.

Joel Dresang is vice president-communications at Landaas & Company.

(initially posted Oct. 31, 2018)

Where there’s a will

Who has a will varies largely by age and socioeconomic status. According to a Gallup poll, 44% of Americans said they have a will.