Learn more

How much to spend in retirement, by Art Rothschild

Knowing the number, by Brian Kilb

Retirement 101: Having a plan, a Money Talk Video with Tom Pappenfus

Having the confidence to retire, a Money Talk Video by Art Rothschild

By Joel Dresang

A couple of weeks before workers were supposed to demolish our kitchen, we heard banging from the basement. Our furnace suddenly (after 24 years) decided to bite the dust at the same time we were starting a long-postponed kitchen update – and considering a trip abroad.

As my wife called a furnace technician, I created a spreadsheet – listing all the anticipated expenses we’re facing now as well as the possible funds we can tap to cover them.

Inspired by panic, I did what too few of us ever do – created a budget.

I had some idea how much these expenses could amount to, but the furnace caught me unawares. The budget wasn’t much work – talking it through with my wife and looking up some numbers. When we were through, we had a clearer picture of how much we can plan to spend. It calmed me by giving me a greater sense that we have control of our finances.

Most Americans don’t think enough about spending. About 34% of workers have estimated their retirement expenses, according to the latest retirement confidence report from the Employee Benefit Research Institute.

“Retirement is the most expensive purchase you’re ever going to make. It makes sense to figure out what it’s really going to cost,” David Blanchett, head of retirement research at Morningstar Investment Management, told Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.

When estimating retirement costs, an often-quoted rule of thumb is 80% of your pre-retirement income. That’s a lazy answer because it’s easier to know what your income is than to track your expenses.

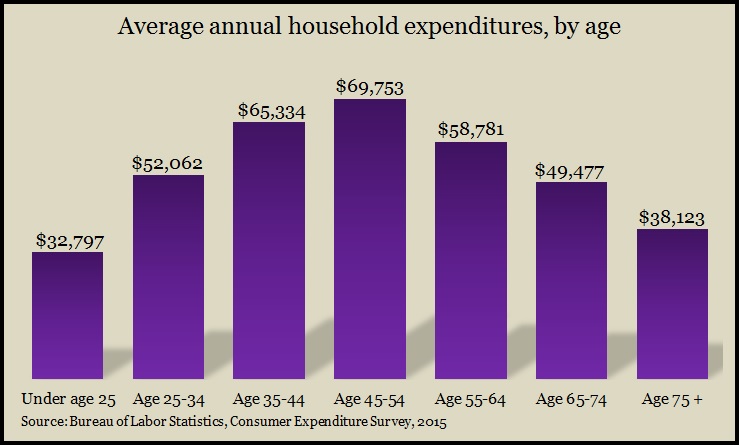

Research supports the intuitive notion that we’ll spend less in retirement than we do while we’re working. Using survey data, the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows household spending rising by age 45 through about 54 and then declining. Even as health care expenses escalate as retirees get older, spending narrows in such categories as retirement savings, transportation, clothes and restaurants.

A study by the Employee Benefit Research Institute showed a typical household spending 5.5% less in the first year of retirement and 12.5% less by the third or fourth year before leveling off. Of course, results varied, with many families splurging right after retirement and then cutting back later on.

Blanchett, from Morningstar, has challenged that 80% rule, reasoning that it’s likely lower for most retirees. Blanchett calculates that the amount of income households need to replace what they had before retirement varies widely, probably ranging from 54% to 87% of pre-retirement levels.

In other words, if you earned $100,000 a year before you retired, conventional wisdom suggests you need retirement income – pension payments, Social Security, investment withdrawals and so on – of $80,000 a year. Blanchett figures you might get by on $54,000. Or you might need $87,000.

That’s quite a range.

And while Blanchett concedes that 70% to 80% of income “is likely a reasonable starting place for most households,” what you actually need to spend depends on your individual circumstances.

That’s why, as tedious as it might seem, tracking what you spend and anticipating your expenses – especially as you near retirement – is a wise way to help plan for the most expensive purchase you’ll ever make.

As opposed to the 34% of workers who told the Employee Benefit Research Institute that they have estimated their retirement spending, 52% of those already in retirement said they have planned their expenses. And their planning apparently paid off because 62% of the retirees said they found their expenses to be about the same or lower than they expected.

For our family, a quick, simple spreadsheet has allowed us to look before we leap. We can see that if we put off replacing some of the appliances, if we economize on some of our options in the kitchen and alter some other plans, we still can manage the remodeling, the furnace – and the trip.

“Retirement is far more complex than accumulation,” Blanchett says. He notes that for all the effort that many of us put into buying a new phone or a new car, we need to be more diligent about planning out what we’ll be spending in retirement.

A line in Tennessee Williams’ “The Glass Menagerie” got a chuckle from the audience I was in last month at the Milwaukee Repertory Theatre. Maybe it sounds funny to the ear, but it’s poignant to consider:

“… (T)he future becomes the present, the present the past, and the past turns into everlasting regret if you don’t plan for it.”

Joel Dresang is vice president-communications at Landaas & Company.