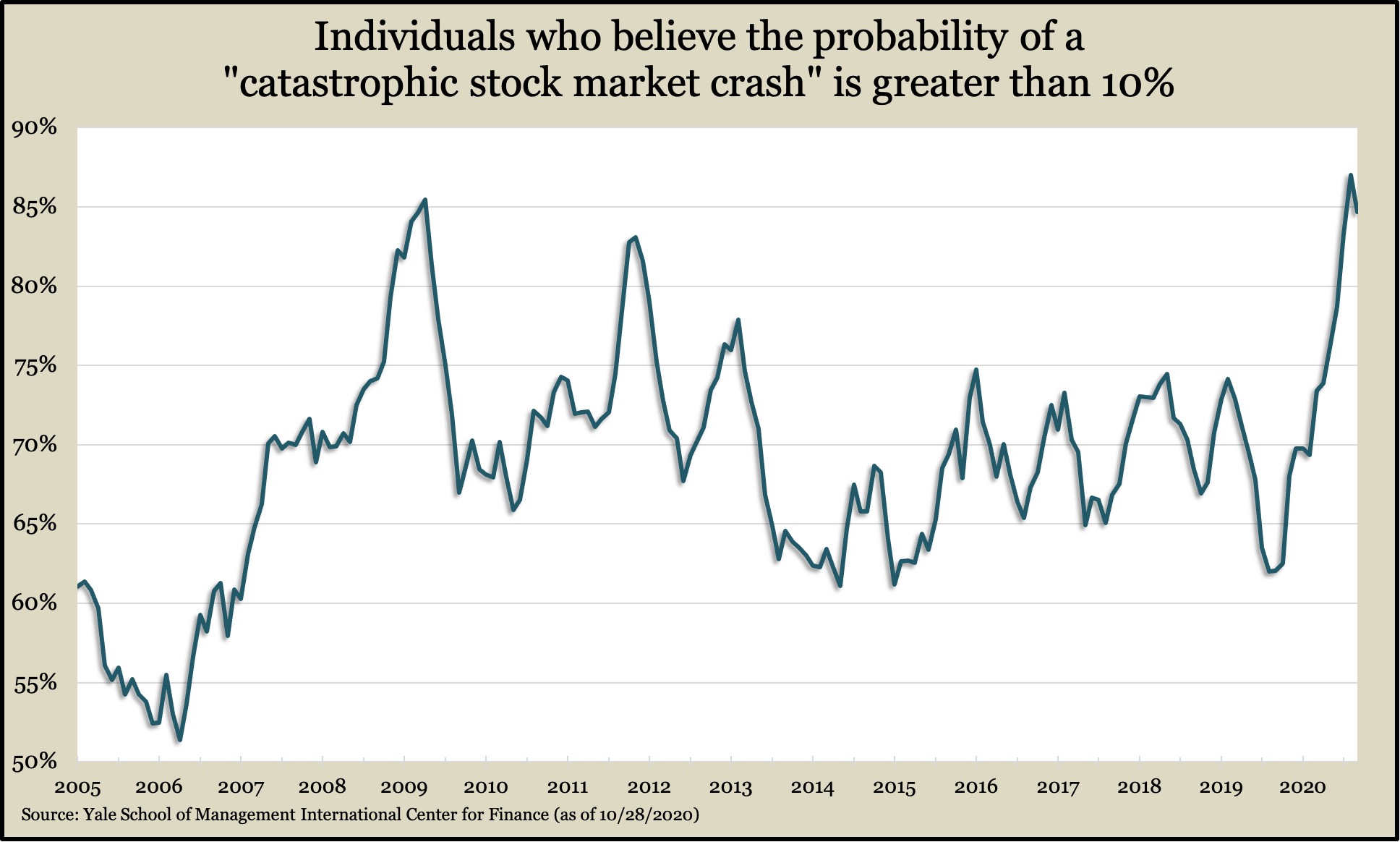

Economists at Yale University have been sounding some sour notes lately on the U.S. financial markets. Researchers with Yale’s decades-long confidence surveys ask individual and institutional investors straightforward questions, such as what they believe the probability is of a “catastrophic stock market crash in the U.S. in the next six months.”

Individual investors were as pessimistic as ever in August, according to survey data. The most recent report shows little improvement.

More than eight in 10 respondents said there’s a greater than 10% chance of a “catastrophic crash” in the next six months, defined by researchers as an experience similar to 1929 or 1987. Considering what has been going on, I can’t blame them for their pessimism. For instance:

- Covid-19 cases are on the rise again after slowing through late summer.

- The economy is mired in a pandemic-fueled slowdown, and labor market gains have weakened.

- A particularly contentious election season seems to have stoked some of the fears.

Many investors could simply be wary that the worst may not be over after wondering how their portfolios escaped the first 10 months of 2020 largely unscathed.

Given the signs, investor fears are certainly reasonable, but what comes next may not be obvious. Consider that the two previous peaks for investor pessimism from the Yale surveys came in early 2009 and late 2011. Both occasions were followed by periods of strong returns for stocks.

Historically, stocks have climbed a wall of worry. It’s one thing to say it, but it’s another to understand why.

Investor sentiment, at its core, is all about capitulation: How bad do you have to feel about the prospects for stocks before you give up and head to cash?

What we find historically is that by the time investors collectively feel their worst, most of the selling has already happened. Then, with all that cash on the sidelines, there is nobody left to sell as stocks begin their ascent.

But just because something happened in the past doesn’t mean we’re set for the same outcome this time around. Notably, valuations are more expensive than during previous periods of elevated investor pessimism, and questions remain about the path forward in this pandemic.

Yet, one of the most meaningful indicators could well be suggesting that the current bout of pessimism may resemble the previous round.

Notably, publications across the country have been writing for months about the piles of cash that investors are sitting on. While that cash doesn’t necessarily signal all the selling is over, it’s a pretty good sign that investors aren’t overextended in risky assets anymore.

Further, those same investors may well get sick of low-yielding money markets at some point and begin to look at the very places they sold from when they first began to get nervous. As a safe harbor in a storm, cash looks great, but the minimal yield does little to move investors toward their final objectives.

I don’t mean to sound overly optimistic. We have plenty of hurdles to overcome, and pessimism can persist, keeping cash on the sidelines long enough to frustrate even the most optimistic investors. However, piles of cash and record levels of pessimism may be just the contrarian indicator that a balanced investor needs at this time to continue to stay the course.

Kyle Tetting is director of research and an investment advisor at Landaas & Company.

(initially posted October 29, 2020)

Send us a question for our next podcast.

Not a Landaas & Company client yet? Click here to learn more.

More information and insight from Money Talk

Money Talk Videos

Follow us on Twitter.

Landaas newsletter subscribers return to the newsletter via e-mail.